The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

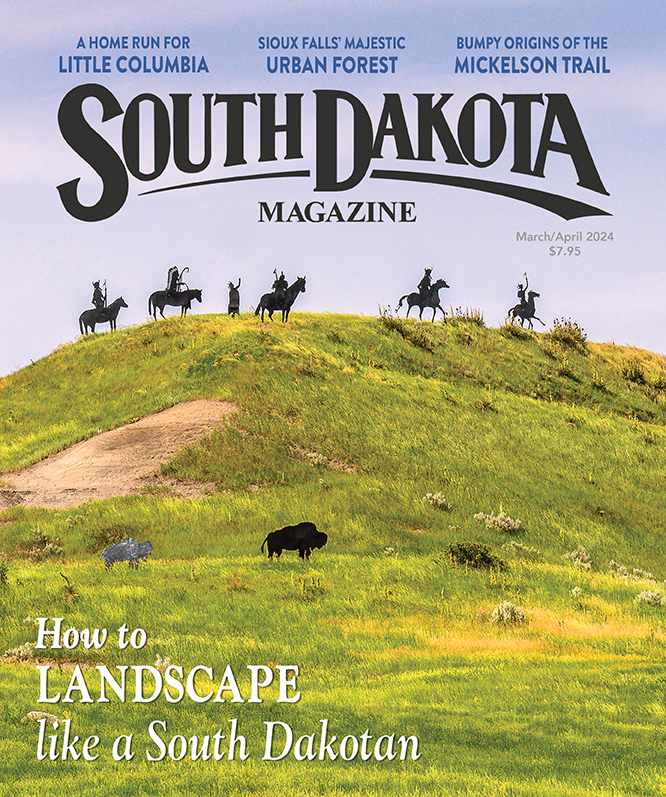

Suspects in Sturgis

|

| Historic Fort Meade was home to Nazi sympathizers during World War II. |

A little less than a year after the United States' entry into the Second World War, the strange soldiers of the 620th Engineer General Service Company arrived at Fort Meade, near Sturgis. On work details they wore blue fatigues, not green. Prisoners of war were typically issued blue fatigues, but no "PW" lettering adorned the 620th's work uniforms.

These soldiers numbered between 100 and 200 most of the time. Despite that small number, writer E.J. Kahn would note after the war, the 620th claimed "the distinction of being responsible for four-fifths of the convictions under the Eighty-first Article of War recorded against the 11.5 million men who served in the army during the Second World War."

Conviction under the Eighty-first Article is deadly serious business: it means being found guilty of aiding the enemy. Members of the 620th were American soldiers, but it didn't come as a complete surprise when some plotted acts for the glory of the Third Reich.

"What made the company unique was that, except for its officers and a cadre of noncommissioned officers, it was filled entirely with men who were suspected of subversive activity or disloyalty," wrote Bob Lee in his book, Fort Meade and the Black Hills.

The army had to prove nothing for a soldier to be sent to the 620th, Lee added. Suspicion sufficed.

At Fort Meade the 620th painted barracks, hauled trash, planted trees, graded a landing area for military gliders and made camouflage netting. They were issued no arms.

Like other Fort Meade military personnel, they were free to live off the post grounds. Many lived in Sturgis or Deadwood apartments and commuted to the fort five days a week. Weekends were spent enjoying the Black Hills' amenities, and pursuing the charms of local young women, many of whom missed boyfriends sent to combat in North Africa, Europe or the Pacific.

Certainly the soldiers of the 620th enjoyed cushy wartime duty, maneuvering their way through pine forests en route to picnics in Custer State Park, rather than through land-mined jungles or sniper-protected villages. The military eventually heard criticism about that, but at the time the army found itself in a bind. Exempting from military service those men who didn't approve of the nation's war policy wasn't fair, plus, doing so would offer an easy out for those hoping to avoid enlistment. At the same time, the army didn't want these men, some of whom were vocal in their admiration of Adolf Hitler, in regions where they could pass information to the enemy or sabotage American war production. The War Department studied maps, decided Fort Meade was about as far removed from the war as a soldier could get, and formed the 620th under a confidential order in October 1942.

Most of the 620th soldiers were of German or Italian descent. Other companies were established elsewhere for soldiers suspected of sympathy for Japan. It should be noted that many men of the 620th wished the United States no harm in the war, and hoped the whole affair would simply end quickly.

Because formation of the 620th was confidential, the Black Hills public didn't know of its makeup, although a few remarked that lots of the men spoke with accents and knew all the lyrics to German beer hall songs. "The citizens of Sturgis, had they known the 620th was filled with soldiers the army considered undesirables, would have been shocked, since they had treated these men as freely and as generously as they had the other soldiers from the fort," Lee wrote.

|

| Stone stables at Fort Meade housed 86 horses each. Located just east of Sturgis, the fort now stands as a National Historic Site. |

Along with being shocked, the citizens of Sturgis likely would have worried the soldiers might try something rash if a militant leader joined their ranks. That leader came along in March of 1943, in the person of Dale Maple.

Maple wasn't typical of the 620th. Maple wasn't German or Italian. Actually, he wasn't typical by any standard of American young men. He was, when he arrived in South Dakota, a 22-year-old graduate of Harvard, where he'd studied government and publicly expressed admiration for Hitler's fascist regime. He attracted enough attention for his views at Harvard that Time magazine once described him as a "native U.S. Nazi." In his hometown of San Diego, as a child, he'd seen his name in the press often as a piano prodigy. Southern California music critics predicted big things for him in concert halls.

Maple graduated from Harvard, with academic honors, in the spring of 1941. He was still on campus doing post-graduate work the next December when the United States declared war. Hours after Maple heard news of Japan's attack at Pearl Harbor, he phoned the German embassy in Washington. He told an official there it looked obvious the German ambassador and his staff would shortly be expelled from Washington, and said he would like to join them when they traveled home to Germany. The embassy official told Maple no.

So Maple joined the United States Army. Had he been sent overseas, deserted and made his way into German territory, he would have had no trouble communicating his Nazi sympathies. He'd learned German and spoke it fluently. But Maple never got near the war. After training as a military radio operator at bases in North Carolina and Maryland, Maple was transferred to Fort Meade in early 1943. The army decided that the support he declared for Hitler at Harvard made him a case for the 620th.

Speaking to South Dakota Magazine 57 years later, just a few weeks shy of his 80th birthday, Maple recalled the 620th was quartered in barracks built for and by Civilian Conservation Corps workers in the 1930s, on the west end of the fort grounds. "We received no military training as such," he said. "Of course, there were no thoughts that we'd be part of the Okinawa invasion."

While Maple's well-documented remarks left no doubt why he'd been sent to Fort Meade, he said some of the others "had no idea why they were in that unit."

Maple rented an apartment in Deadwood, found he had lots of time for reading and backroom gambling, and made some friends in Deadwood's bars. Black Hills acquaintances recall him as tall, handsome, well mannered, soft-spoken and a remarkable piano player. He had one minor brush with the law in Deadwood when picked up for tampering with someone's car.

The 620th liked Spearfish Canyon. In the summer of 1943 the soldiers would sometimes rent a cabin there for weekend parties where beer flowed and rousing choruses of German beer hall songs rattled the windows. The army suspected espionage might be being plotted in the cabin and bugged the place. Surveillance uncovered nothing.

But it was proven later in court that the army had good reason to worry about subversive plots. Maple and a few friends in the 620th spent time in the Black Hills, in the words of E.J. Kahn, "exploring, largely in conversation, courses of action they might take to demonstrate their disaffection — espionage, desertion, mutiny, sabotage, guerrilla warfare against the United States, and so on."

|

| Site of Orman Dam POW Camp north of Fort Meade near Belle Fourche. |

Helping German prisoners of war escape appealed to the conspirators, but no prisoners came to Fort Meade until after they had left. The first week of December 1943, the 620th transferred to Camp Hale, Colorado, 120 miles west of Denver. On one hand, the soldiers disliked the move because everyone but married men had to live at the post. On the other hand, 200 German prisoners were also quartered there.

Imagine Hogan's Heroes in reverse. The German POWs had a still for making schnapps, acquired a pistol and American military uniforms, and regularly got themselves out of their compound and allowed visitors in. The 620th men, in blatant violation of regulations against fraternization, won the prisoners' confidence and friendship with gifts of candy, tobacco and whiskey. When POW Erhard Schwichtenberg said he wanted to see the American West, the 620th got him out for a couple days and drove him several hundred miles through Colorado. Nobody missed him. When Maple got a three-day leave, the only place he wanted to visit was the inside of the POW compound, where he spent the entire period, wearing a German uniform and drinking schnapps — and learning that Schwichtenberg and another prisoner named Heinrich Kikillus wanted to escape as much as Maple wanted to help them.

Maple bought a decade-old Reo sedan. On February 15, in broad daylight, he simply drove the car to a rendezvous point just off the post grounds, and Schwichtenberg and Kikillus strolled away from a work detail and climbed in. Nobody noticed for more than 24 hours that the prisoners were missing and Maple was AWOL. By the time they were missed, the trio was far south down U.S. Highway 85, in New Mexico, implementing a Black Hills plan that called for getting to Mexico first. From there the idea was to reach Argentina and secure passage by ship to Spain, and from Spain travel to Germany.

After two flat tires and an electrical problem, Maple got the car within 17 miles of Mexico. Then he ran out of gas, and the three companions hiked cross-country into Mexico by night. A Mexican border patrolman stopped them 3 miles inside Mexico on the afternoon of February 18, and turned them over to United States authorities.

At a military trial two months later at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, Maple said the escape had been merely a ploy to call public attention to the injustice of companies like the 620th. Further, he claimed, he'd only pretended to be a Nazi at Harvard in hopes of winning German scholarship money to pursue post-graduate studies at the University of Berlin. Nobody bought his stories and he was convicted of desertion and aiding the enemy, and sentenced to death. Three fellow conspirators in the 620th — Paul Kissman, Theophil Leonhard and Friedrich Siering — were court-martialed and sent to prison. The German prisoners, it was noted, simply had exercised their right and duty to attempt escape.

After Maple's death sentence was handed down, nobody in the military or federal government seemed to want to see it carried out. The secretary of war sent a memo to President Franklin Roosevelt, saying of Maple: "While he is undoubtedly legally sane and responsible for his despicable acts, under all the circumstances I am unable to escape the impression that justice does not require this young man's life. I feel that the ends of justice will be better served by sparing his life so that he may live to see the destruction of tyranny, the triumph of the ideals against which he sought to align himself, and the final victory of the freedom he so grossly abused."

Maple did live to see the triumph of American ideals and freedoms, and, in fact, to prosper by them. Roosevelt commuted his sentence to life in prison, and later it was reduced to 10 years at Leavenworth federal penitentiary. He proved a model prisoner and was still a young man when released in the 1950s.

“I came back to California and got into a venture building commercial fishing boats," he said. "I learned about insuring boats, and that led me into the marine insurance business worldwide." He never returned to the Black Hills.

It is possible the Black Hills would have forgotten Maple and the entire 620th had it not been for E.J. Kahn's series of articles about the company and Maple's trial, published in 1950 in the New Yorker magazine. Suddenly people who had wondered about those soldiers' accents and their knowledge of German beer hall songs had answers.

As for Fort Meade, the War Department declared the post surplus the same month Dale Maple went to trial, April of 1944. Fort Meade then became a Veterans Administration hospital.

"Ironically, aside from the station complement, the 620th was the last company-sized army unit stationed at Fort Meade before the post's abandonment as a military installation,” Lee wrote. “It was a strange ending for a garrison that had included many of the army's most highly regarded and decorated outfits during its long years of service."

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the November/December 2000 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments